It’s here: Charlie Kaufman’s return to directing. We have a lot to talk about. First let me give you a (criminally) abridged recap:

A young woman goes on a road trip to visit her boyfriend Jake’s parents at his childhood home on a snowy winter afternoon. She has been thinking of ending things despite their “special” kind of connection. They have a tense and layered discussion on the way. When they arrive at the house, they meet Jake’s family. Memorabilia from his childhood (photos, art, reading material, etc.) crosses over with Jake’s girlfriend’s, and his parents are completely off kilter, and rapidly age and de-age during the visit. It’s an odd night, and everyone seems off. When Jake and his girlfriend leave, they stop at a Tulsey Town ice cream store and buy two blizzard-like shakes. They leave and get sick of how sweet they are, so they don’t eat them. Jake feels so compelled to throw them away that he stops at a nearby high school in the middle of the snowstorm. After throwing the ice cream away, Jake initiates some romance with his girlfriend. He sees someone watching them and gets violently angry and leaves the car. The young woman follows him inside, and their written reality reaches the end of its third act.

What’s really going on here? The story is about a lonely janitor suffering from a drowning kind of anti-actualization. He saw a beautiful woman at a bar, and fantasized about a younger version of himself having picked her up. The relationship between “Jake” and the younger woman is a fantasy. The visit to the parents’ home is a fantasy. The reality is the janitor watching movies, cleaning a high school every night, and losing his grip on what’s real before ultimately he ends things.

That kind of gimmick is old, and generally a treachery to modern storytelling, but the writing in Charlie Kaufman’s adaptation of the book I’m Thinking of Ending Things is oh-so-gorgeous. Though we might have come to expect some mind-bending, the unique brand of Kaufman surrealism is rampant in this movie, which sometimes muddles the main character’s attitude, and the reality we are meant to believe seems kind of discretionary– that is until the very end.

The fantasy dissolves towards the very middle of the movie, but it continues moving through the characters, whatever form or names they take. From the beginning, the concern of the janitor, and so the young woman, is the unstoppable passage of time. The young woman believes that it moves through us, that it doesn’t carry us forward. We are stationary and let time affect us. This is a far cry from Synecdoche, New York, where we were spending most of the movie trying to catch up because it’s moving forward so quickly. Because of this, some very interesting things happen while Jake and the young woman are talking in the car. The dialogue has a nuance that is uncharacteristically careful of Kaufman. In the past he has been much less subtle. When they talk, you can feel the outside influence. The way they communicate, though they play different characters in the janitor’s head, is very much the same.

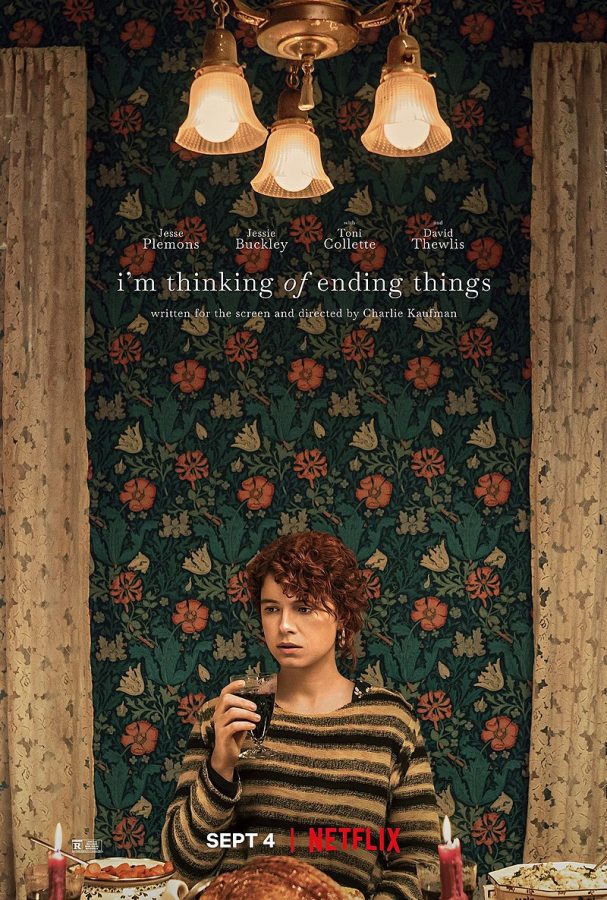

The poem that the young woman reads in the car on the way to Jake’s parents’ house acts like a chorus for the next two acts, and the delivery from Jessie Buckley is haunting. The eye contact she makes with the camera paints the scene somewhat Bergman-esque, but with something much more sinister behind it.

When they are driving home, their discussion of A Woman Under the Influence nearly becomes a Criterion Observations on Film Art edition the way the young woman adopts a Katharine Hepburn accent and smokes a cigarette. At one time she even transforms into the character from the fake Robert Zemeckis film the janitor was watching, which artfully hints at the janitor’s awareness of his condition.

This has to be one of the best scripts we have seen realized in the last five to 10 years. The challenging pace and modernist cinematography fit this picture into the new decade’s zeitgeist of experimental cinema. The year 2019 really set the stage for what was to come, and with the first real elevated American picture of the decade, we see those fruits ripening.

The casting is genius. Jesse Plemons and Jessie Buckley make the roles singular and intelligent. There are some moments where Toni Collette overacts, but her extravagance is grounded by David Thewlis’ beautifully tempered performance as Jake’s father. The music by Jay Wadley is not a far cry from Kaufman’s former partner Jon Brion. Wadley’s score is haunting, nostalgic, at times very sweet, and always very moving. The cinematography by Łukasz Żal is captivating. The motion is sharp — something we might have seen from the likes of Kevin Hayden — and the palette consistently cool and melancholy. The 4:3 aspect ratio suffocates the subjects, and makes the audience feel like a voyeur. Unexpectedly, this being among the many recent at-home releases contributes to the feeling of voyeurism. This film does a fantastic job balancing melancholy and anxiety through its expert visual storytelling.

Charlie Kaufman is one of the best living writers, and we can only hope we don’t have to wait as long for his next picture to touch our undeserving world. His characters are here, as they usually are, glaringly awkward, and they still turn out more human than most characters in cinema. Despite this being an adaptation, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is Kaufman’s most sophisticated script yet. I recommend you watch the film at least twice, more if you have the time. For its lasting emotional resonance, incredible writing, and sheer beauty, I award this film a five out of five.